Several miles westward of the Chateaugay Mine

and on the same strike as the Chateaugay ore bed, is an old opening (81

Mine), which had evidently been worked to a considerable extent at some remote

period. A shaft had been sunk from which quantities of waste, which today

would be good ore, had been thrown out and left. Trees of considerable

size had grown over some of this waste pile. Lloyd N. Rogers purchased

this land containing the mine in 1822 and in the following year a trapper,

Collins, is credited with having found the body of ore, practically phosphorous

free, known as "Chateaugay".

Even after the ore bed was known, it excited little

interest among capitalists, for it was far from lines of transportation,

lying in a region abounding in natural obstacles, held to be practically

insurmountable against the building of roads. So not until 1868 were the

first steps taken toward utilizing this treasure. In that year Foote, Weed,

Meade & Waldo made a contract with Edmund L. Rodgers of Baltimore, the

son of Lloyd N. Rodgers. Soon after they obtained possession of the

property. Even then little development was done in the next five years.

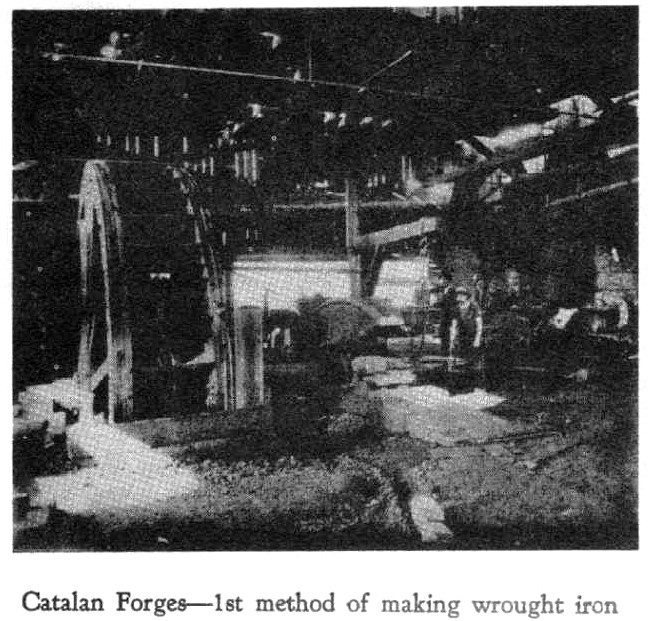

Small groups of men dug ore during the summer, piling

it on the surface to be loaded during the winter months and hauled by horse-drawn

sleighs through the wilderness to the Catalan forges on the Saranac

River. In 1874, twenty Catalan forges together with charcoal

kilns were erected at the outlet of the Chateaugay Lakes at Belmont.

All the charcoal and ore were moved on the lake in barges hauled by steamboat

in the summer and by horses and sleds in the winter. The blooms and

billets of almost pure iron were hauled to Chateaugay and shipped by rail

to the steel mills in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

The Catalan forge furnace in which iron was

made direct from ore, was an open hearth, similar to a black-smith forge

but larger in size. The hearth was about 2 1/2 by 3 1/2 with a stack

20 to 25 feet high. Blast was furnaced either by a bellows or means of a

trompe. The pipe that carried the air to the hearth was coiled in the stack

of the furnace, the object being to preheat the blast, thus saving fuel.

The operation consisted of a charcoal fire, stimulated by a blast of air,

to which iron ore and charcoal in small quantities were added alternately

by the bloomsmen who also regulated and adjusted the fire until the batch

of iron, called a "loupe", weighing about 300 pounds was made. This

usually took about three hours.

Go to Page 1 of The History of Lyon

Mountain.

Go to Page 3 of The History of

Lyon Mountain.

Go to Mining History for The

History of Mining in the North Country.

Go to Page 5 of The History of Lyon

Mountain.(for article on Lyon Mt. and Mineville)