Mining for Souls

Page 47a =72

Standish Furnace page 2

Standish Furnace page 2

When wood is heated without contact of air, it

breaks up into certain volatile products and a fixed carbonaceous residue

known as charcoal. The charcoal retains the structure of the original

wood, is black in color, very light and extremely porous. Good charcoal rings

when struck, and while it breaks easily, is not readily crushed by ordinary

pressure. When ignited, it burns without flame.

When wood is heated without contact of air, it

breaks up into certain volatile products and a fixed carbonaceous residue

known as charcoal. The charcoal retains the structure of the original

wood, is black in color, very light and extremely porous. Good charcoal rings

when struck, and while it breaks easily, is not readily crushed by ordinary

pressure. When ignited, it burns without flame.

The average charcoal retains almost the bulk of the priginal

wood, but only 20 to 25 percent of the weight. The weight of average charcoal

is 20 pounds to the bushel or approximately 100 bushels to the ton. In

kilns that had recoveries, they would make aproximately 45 pounds of charcoal,

two gallons of wood alcohol, and 75 pounds of calcic acetate from one

load of wood. It takes 1.44 as much air blast by volume to burn a pound

of charcoal. A charcoal furnace with a capacity of 150 tons daily, required

a cordwood pile a half mile long. Hardwood, such as maple and birch, makes

the best charcoal for blast furnaces, but softer wood can be used. The

best charcoal is made when the trees are cut before the sap is up and the

wood is stacked in cordwood piles to dry out.

Charcoal was an ideal fuel for blast furnaces; its low

combined carbon and high volatile matter makes its reactivity the greatest

of all. The largest charcoal blast furnace in the world was at Sault

Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada, which make the world's record of 173 tons of

pig iron in 24 hours.

The advantages of charcoal over coke: first. the furnace

consumes considerably less charcoal than coke per ton of pig iron.

Second, only one-third as much limestone per ton of pig iron is required

in a charcoal furnace. Third, the amount of blast of air required for a

charcoal furnace is only 65 per cent of that of coke. Fourth, the critical

temperature in a charcoal furnace may be lower than a coke furnace.

The one serious disadvantage of charcoal was the difficulty in getting a

sufficient supply of good charcoal.

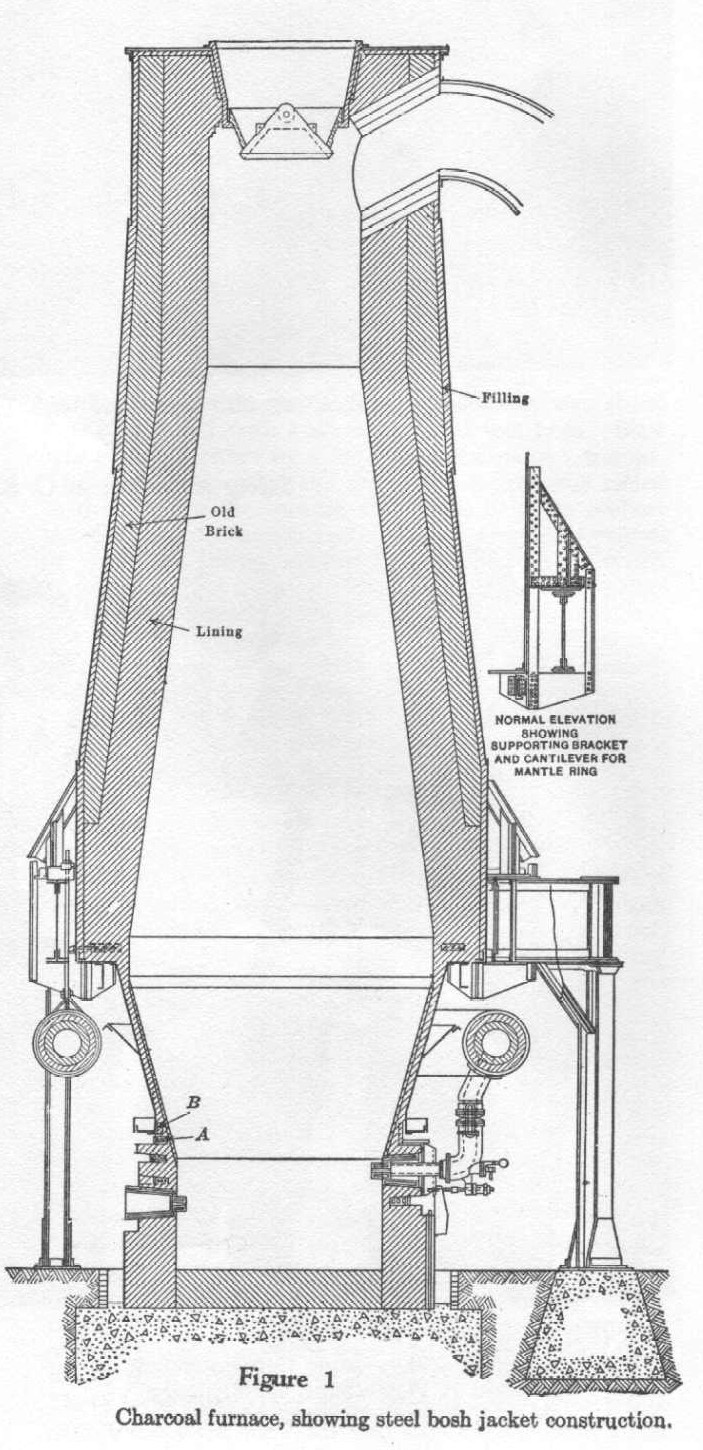

In 1885 the company began the erection of a blast furnace

at Standish. They also extended the railroad from Lyon Mountain to

that point and later to Loon Lake in order to reach the charcoal kilns and

woodland that it owned. In the next year the Catalan forges at Standish

were temporarily abandoned, and the making of pig iron was commenced in

the new blast furnace, using charcoal as fuel. This resulted in the

development of an entirely new market, pig iron being an entirely different

product from "bloom iron" produced by the Catalan forges. However,

the steel-making by the Bessemer process was gaining by leaps and bounds

in this country, and the Chateaugay iron being extremely low in phosphorus,

was in great demand. The village of Standish expanded and really began

to make industrial history.

With the major depression of 1893 the company moved

the forges from Belmont to Standish so that "bloom iron" and pig iron could

be made at that one point and shipped by rail.

As steelmaking by the Bessemer process and the making

of wrought iron by the puddling process increased, demand for Catalan forge

blooms decreased. This was not on account of quality, but because these

new processes could make serviceable wrought iron and steel for less than

half the cost a Catalan forge blooms. As a result the American bloomery,

which for many years had been the backbone of the iron and steel industry

of the Adirondacks, was doomed. The company subsequently abandoned its operations

and continued making low phosphorus pig iron in the blast furnace using charcoal

as fuel.

In 1903 because

of the increasing difficulty of securing a sufficient supply of charcoal

for the blast furnace and the fact that by this time coke had replaced charcoal

in most of the blast furnaces in the country and could be secured at a much

lower cost, the Standish furnace was changed from a charcoal to a coke furnace.

Between 1903 and 1907 much of the light equipment was replaced with heavier

and more substantial equipment. The output of pig iron was then considerably

increased.

Sources:

Adirondack Museum photos, Blue Mountain Lake, NY;

History of Clinton County, New York;

from History of Mining of Chateaugay

Ore and Iron Company.

Go to Page 1 of The History of Lyon

Mountain.

Go to Page 3 of The History of

Lyon Mountain.

Go to Mining History for The

History of Mining in the North Country.

Go to Page 5 of The History of Lyon

Mountain.(for article on Lyon Mt. and Mineville)

Go to Page 48 of Mining for Souls.

Back to Page 46 of Mining for

Souls.

Go to Page 1 of Mining for Souls.(cover

page)

Rod Bigelow

Box 13 Chazy Lake

Rod Bigelow

Box 13 Chazy Lake

Dannemora, N.Y. 12929

rodbigelow@netzero.net

rodbigelow@netzero.net  BACK TO

THE HISTORY PAGE

BACK TO

THE HISTORY PAGE

BACK TO

BIGELOW HOME PAGE

BACK TO

BIGELOW HOME PAGE